Bega's Ambitious Plan for a Circular Economy by 2030

Barry Irvin, a prominent Australian businessman, envisions Bega becoming Australia's leading circular economy by 2030. Since taking over Bega Cheese, now known as Bega Group, in 1991, Irvin has transformed the small dairy cooperative into a food company with an annual turnover of $3 billion.

Irvin's commitment to circularity was sparked by a Dutch banker's explanation of the Netherlands' pioneering efforts in low-emission, sustainable circular practices. He described circularity as a "virtuous circle" benefiting the economy, society, and the environment.

For the past two years, Irvin has been rallying support from business, government, and academic leaders for Australia's most extensive circular economy experiment. He aims to achieve 30% circularity by 2030 and 50% within the following decade, aligning with European targets. "In the Netherlands, the goal isn't net zero by 2050; it's to be a fully circular economy by 2050," Irvin noted.

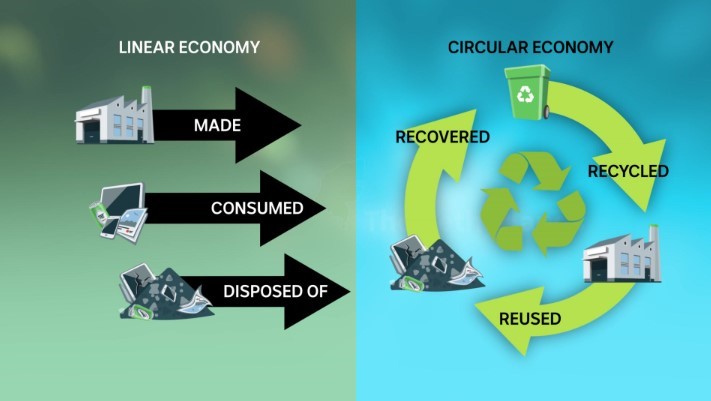

A circular economy involves maintaining materials in the economy at their highest value for as long as possible, eliminating waste and pollution, and regenerating natural systems. According to Circularity Australia CEO Lisa McLean, achieving net zero in Australia is impossible without adopting circular practices.

The Bega Valley Shire Council is an enthusiastic participant in the circularity project. The council already operates a recycling center and an organic waste collection service. Last year, 1,000 tonnes of food and garden waste were diverted from landfills. Despite these efforts, 19,000 tonnes of rubbish were still sent to landfills, a figure rising faster than population growth. Tim Cook, the council's waste strategy coordinator, believes community support for the circularity project could reduce landfill waste to single digits.

Several waste streams in the Bega Valley are already being reused. Bega Group's dairy factory boiler runs on wood waste, with the resulting fly ash used as a lime replacement on pastures, saving the company $200,000 annually in landfill fees. Additionally, a new evaporator extracts valuable milk minerals from liquid whey waste, and 1.2 million liters of wastewater are used daily for hay pasture irrigation.

Seaweed researcher Pia Windberg sees potential in using factory wastewater for onshore seaweed farms. "We've developed a unique Australian green seaweed, know how to dry it, incorporate it into foods, and have just achieved our first export," Dr. Windberg stated, envisioning the industry reaching 10% of the wheat industry's size.

In the next two years, a $19-million National Centre for Circularity will be established in Bega, funded by a $5 million donation from Bega Group and contributions from the New South Wales government. Kristy McBain, the state's minister for regional development, praised Irvin's strong community connections, noting the involvement of Rabobank, KPMG, Deloitte, Charles Sturt University, the University of Wollongong, the local council, and both state and federal governments.

Irvin believes the Bega Valley is ideal for the trial due to its manageable size. "We can measure everything in this valley," he said. "We can quickly determine what works and what doesn't, then share that knowledge. I want to make people envious and inspire them to emulate our efforts."