Call for Increased Responsibility

Nigeria's Environment Minister, Balarabe Abbas Lawal, emphasized that while China and India are still developing, they are far ahead of countries like Nigeria. He called for these nations to contribute to climate finance.

"China and India should not be in the same category as African countries or the small island states most vulnerable to climate change," he said. Similar sentiments were echoed by other delegates, who argued that the resources and influence of these nations demand a greater commitment.

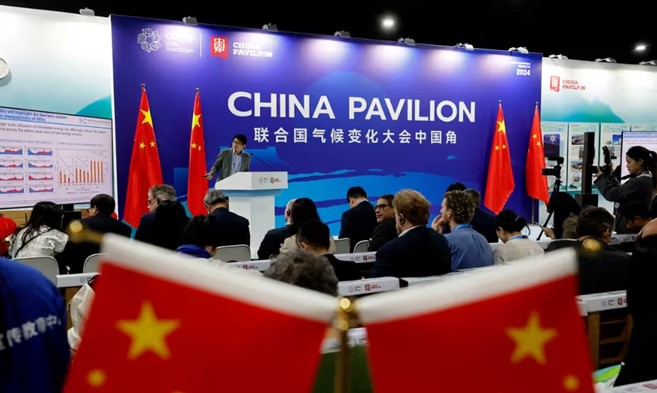

China and India's Role in Climate Finance

China, the world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases and the second-largest economy, currently faces no formal obligation to provide financial aid to developing countries under the UNFCCC. While China has contributed $4.5 billion annually to climate finance between 2013 and 2022, much of this funding reportedly comes with conditions, often tied to loans that burden poorer nations with debt.

India, the world's fifth-largest economy, remains eligible for climate finance, with its representatives arguing that the country's low per-capita income ($2,800 compared to $35,000 in the US) justifies its developing country status. Vaibhav Chaturvedi, a senior fellow at India's Council on Energy Environment and Water, stated, "An acceleration to a green economy without climate finance is unthinkable for India."

A Push for Updated Classifications

Delegates, including Colombia's Environment Minister Susana Muhamad, called for an overhaul of the current system, deeming the developed and developing country categories obsolete. The Paris Agreement, like the UNFCCC, relies on these classifications, complicating efforts to redefine responsibilities.

The focus of COP29 has been to establish a new collective financial goal, as developing nations require an estimated $1 trillion annually to reduce emissions and adapt to climate impacts. Rich countries have been slow to meet existing pledges, intensifying tensions over the roles of emerging economies like China and India.

Historic Emissions and Future Obligations

While India defends its position by citing lower historical emissions, China's cumulative emissions have surpassed those of the European Union. Critics argue that China, as a major economic power, should release more transparent data on its climate finance activities.

Advocates for retaining China and India's developing country status, like Li Shuo of the Asia Society Policy Institute, warn that forcing these nations into a "developed" category could damage trust and cooperation. Conversely, others highlight their roles as indirect contributors through multilateral development banks, suggesting these contributions should also be accounted for.

The Way Forward

The debate reflects the broader challenges of balancing equity and responsibility in global climate action. As negotiations continue, the question of how to fairly classify nations like China and India remains pivotal to achieving a unified and effective global strategy against climate change.